In our previous post we explored TCP basics which layed the groundwork for our didactic web server called turbine. “A turbine is a machine for producing continuous power in which a wheel or rotor, typically fitted with vanes, is made to revolve by a fast-moving flow of water, steam, gas, air, or other fluid.”, similarly our turbine will convert requests into work as we’ll see in the following posts!

Introduction

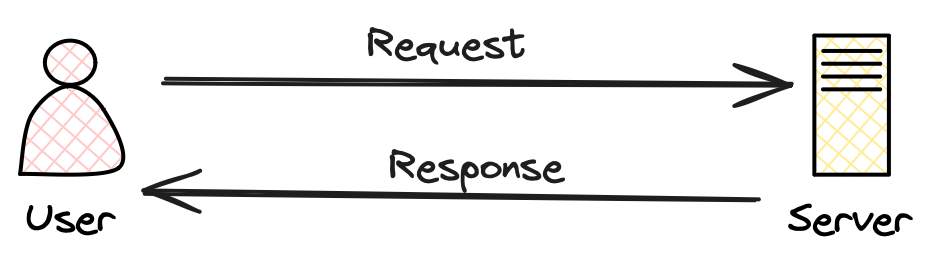

At a very basic level a web server will receive requests from a client and will execute them before returning a response to the client. This is also called the client-server model in which the client waits for a response from the server.

Looking at the diagram below, we want to understand what the server is actually doing before producing a response.

How servers serve

Well, before serving anything to the client, the server has to understand the request. In our case we are talking about an HTTP request. HyperText Transfer Protocol defines the model of communication between the client and the server. For in depth details you can look into this RFC. HTTP version 1.1 rfc defines the methods, message structure and much more without the details of the later versions so it should be easier to follow.

Generally speaking, an HTTP message will consist of headers and body. The headers are providing information about the request (what method are we using - GET/POST/DELETE etc, what content type, what is the content length etc).

So the first job of turbine will be to understand headers.

Just got a request

The GET method is used by the client when they want to retrieve something from the server. For example when you access https://google.com your browser does a GET request to their server and the server returns the google page in response which your browser then displays.

So let’s look at some rust code for parsing a simple GET request.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

let mut buffer = [0; 1024]; // Adjust buffer size as needed

let mut request = Vec::new();

loop {

// don't worry about the unwrap for now, we'll explore

// error handling in the next post.

let bytes_read = stream.read(&mut buffer).unwrap_or(0);

if bytes_read == 0 {

break; // Connection was closed

}

request.extend_from_slice(&buffer[..bytes_read]);

// Check if the end of the request is reached

if request.ends_with(b"\r\n\r\n") {

break;

}

}

let request = String::from_utf8_lossy(&request).to_string();

Let me explain this snippet bit by bit. First you want to create a buffer where we read in chunks of 1024 bytes, and the request which is our final result. We start reading from the TCPStream in a loop, appending everything we read to the request. We stop only if reading doesn’t return anything or if the end of the request is reached (HTTP defines the end of a request as 2 newlines written like \r\n\r\n).

In the end we convert the vector of bytes that we have to a String, replacing all the non utf8 bytes with � (this is done by from_utf8_lossy method of String).

Parsing

We obtained a request in the form of a String, what now? Let’s try to find out what resource the client is requesting.

Below is an example of a possible get request that is looking for the resouce /foo. There is no body, only headers, separated by a new line and the first line as we can see contains exactly 3 things -> method, resource, version. These things are predefined by the protocol and are not arbitrary, so we can count on this when parsing.

1

2

3

4

> GET /foo HTTP/1.1

> Host: 0.0.0.0:12345

> User-Agent: curl/8.1.2

> Accept: */*

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

let lines: Vec<_> = request.split("\r\n").collect();

let first_line = lines.first().ok_or(ParseError::EmptyRequest)?;

let words = first_line.split_whitespace().collect::<Vec<_>>();

if words.len() != 3 {

return Err(ParseError::InvalidRequest);

}

let resource = words[1].clone();

The above snippet is naively parsing the request to obtain the resource. Now our server can finally make a decision, it can check if it knows how to respond to that request and serve its client. Because this post is getting a bit long I will leave that as an exercise to the reader.

Outro

Here we are on the other side. We managed to parse our first request and now turbine understands more of what its clients want from it. In the next post we will revisit the structure of turbine and leverage the Rust type system to make it more robust and more resilient to errors.