This blog post summarises some aspects of borrowing and lifetimes using Rust.

Disclaimer: This blogpost represents my personal notes from various sources such as “The Rust Programming Language” book or various internet articles. No copyright intended.

Ownership

Rust has a very clear set of rules that describe its ownership model. The core concept is that each memory location should have a single owner at a time. Of course, with such a strict rule not much can be achieved so rust introduces the concepts of “move”, “borrow” and “lifetime”.

Move

Move usually happenes through assignment and states the fact that you moved a value let’s say from variable A to variable B, making the former invalid for later use.

1

2

3

4

5

6

let a = String::from("I will be moved");

let b = a;

println!("{b}");

println!("{a}"); // This line will cause the error below.

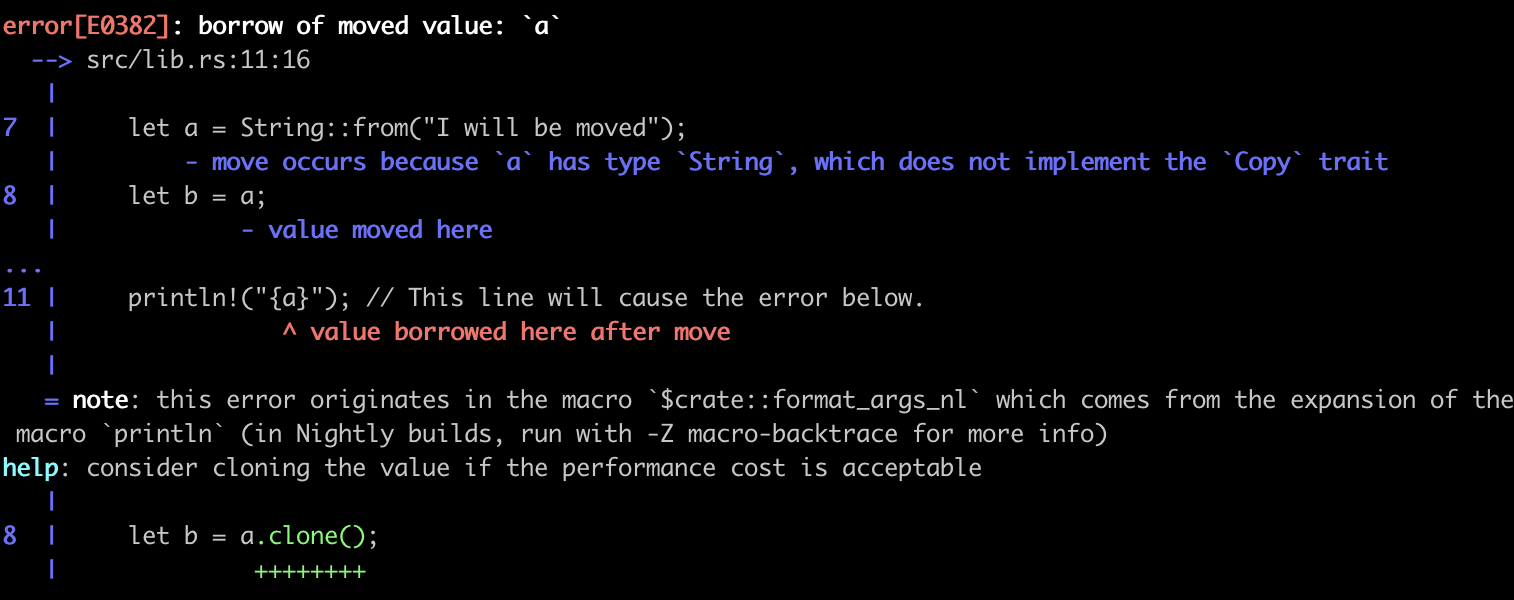

As we can see above, we are not allowed to reuse a moved value. The rust compiler won’t even compile our code to protect us from common bugs caused by moved values. Its errors are very verbose and besides the colored description of why it failed to compile it comes with a suggestion of what you should do in this case(a.k.a clone the string instead of moving it).

Borrow

What if we do not want to move the value out of our variable and we don’t want to clone it either (Cloning is an expensive operation and involves another allocation)?

Rust allows you to borrow values, by creating a reference to them.

1

2

let a = 5;

let b = &a; // Referencing the value stored in a

There are 2 different types of references:

Shared references:

1

2

3

4

5

-> There can be as many of these as you want at the same time.

-> You are not allowed to mutate the initial value

-> Also known as immutable references.

Exclusive reference:

1

2

3

4

5

-> There can be only one exclusive reference at a time

-> You can mutate the initial value which you borrowed.

-> Also known as mutable references

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

// Shared references

let a = 5;

let a1 = &a;

let a2 = &a

// Exclusive reference

let mut c = 6;

let c1 = &mut c;

let c2 = &c;

// This will compile as it is, but if we use the mutable reference

// the compiler will complain that c is mutably borrowed as well as

// immutably borrowed. Uncomment the line below to see the error.

// println!("{}", c1);

Lifetimes

Lifetimes are the reason the above code compiles and runs (without the print statement of course). Why is that? Rust attributes each value a lifetime and it tracks each lifetime throughout your codebase. A lifetime is defined by 2 boundaries:

1

2

-> Where the value is defined

-> Where the value is last used before it goes out of scope.

Rust applies the RAII principle to determine when a lifetime should end, and keeps track of lifetimes using a graph-like structure.

In the above example the life of c1 starts where we declare the variable and ends in the same place because there is no usage of c1 after that line. Hence we can borrow c again in the next line as a shared reference.

If we uncomment the print statement, the compiler figures out that the lifetime of c1 did not end so it won’t allow a shared reference before that point.

Temporary values

Let’s take a look at a more tricky lifetime example.

We will define a function that takes as argument a reference to a string and returns it in the end. When a reference is returned Rust will try to infer its lifetime (we won’t cover the lifetime elision rules in this post). In our specific case the compiler will be able to infer the lifetime of our return value.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

fn sharing_a_string(s: &str) -> &str {

println("I borrowed this string: {}", s);

s

}

fn main() {

// Working example

// let s = "Hello world";

// let _ = sharing_a_string(s);

// println!("After borrowing the string is: {}", s);

let s = sharing_a_string(String::from("Hello temporary world").as_str());

println!("After borrowing the string is: {}", s);

}

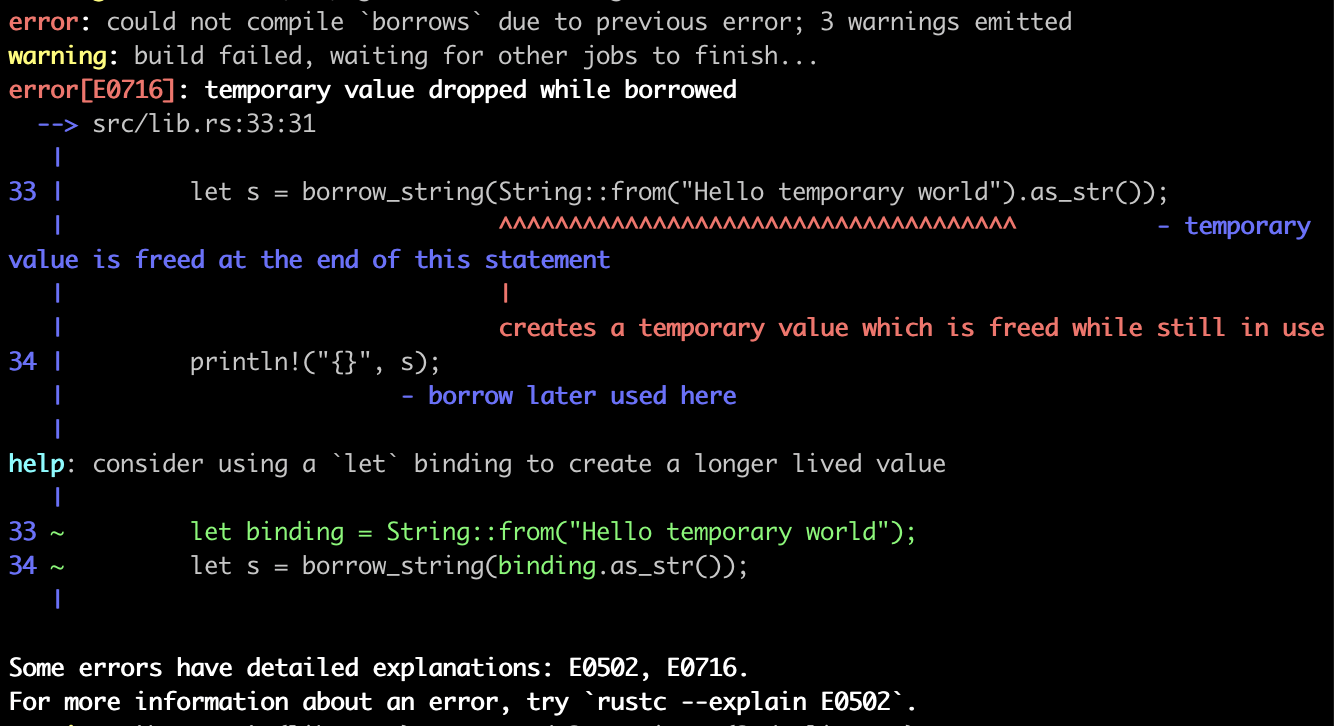

In the snippet above the commented lines follow the compiler suggestion of defining the variable first and then calling the function. In our case, we create the String inside the function call and take it’s reference, then the String will be dropped. The function will try to return a reference to a dropped String, which makes the rust compiler very unhappy. The compiler notices you are trying to use (print to the console) the borrowed value which was freed during the function call, hence the error.

Conclusion

Eversince I started learning Rust I learned to use some computer science concepts (such as references or lifetimes) in the way they are supposed to be used. This article aims to cover the basics of Rust ownership model, but it is not meant for Rust developers only. We barely scratched the surface, we will explore ownership even more in the upcoming posts.